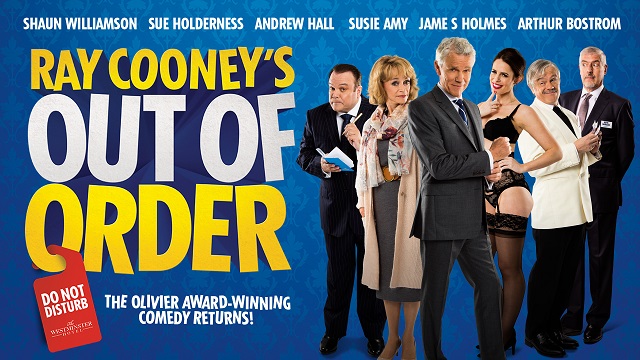

Ray Cooney’s play OUT OF ORDER has been given a facelift to bring it up to date and will visit the Theatre Royal Brighton week commencing 20th March. With a career spanning seven decades in Showbusiness, Ray Cooney is one of the country’s most respected playwrights. Here he tells us about his plays and Out of Order in particular as well as giving us insights into successful career.

How does it feel to be celebrating your 70th year in the business?

[Laughs] It feels like nothing. I started out as a 14-year-old boy actor and I’ve never gotten up any day of my life over the last 70 years and not looked forward to when I’ll be in a theatre, rehearsing, directing, performing or whatever. I love it.

Did you ever imagine when you stepped out on stage in the 1940s that you’d still be in showbusiness seven decades later?

Well, all I ever wanted to do was be an actor. I wanted to be Olivier or Marlon Brandon or even Danny Kaye because I loved comedy. I’ve never been any good at saying no. I didn’t want to be a writer, I didn’t want to be a director, I didn’t want to be a producer and I certainly didn’t want to run and own theatres [laughs] and I shouldn’t have done either of the last two. But one thing segued from another and, as I say, I’ve loved every day of the last 70 years.

Why did you decide to start the celebrations with an updated version of Out Of Order?

What I have been doing fairly recently is encouraging some young producers because that’s what we need. Tom O’Connell is one of those and he learned that I’d been in the business for 70 years so he came up with the idea of doing one of my plays. We discussed which one and I do have a very soft spot for Out Of Order. I know that Run For Your Wife ran for eight years in the West End and all the plays have been done around the world – that’s the most amazing thing. They’ve been translated into probably 30 or 40 languages. They’re done in the Ukraine; think what’s going on in the Ukraine and people still want to laugh. I think that’s what has sustained me over the years. Oftentimes if I’m not appearing in one of the plays and I’m standing at the back as a director, to watch people throw their heads back and nudge each other and point at the stage and laugh is wonderful. I feel I’ve almost been a doctor over the years.

Why do you have such a soft spot for Out Of Order?

Of all the plays, it’s really complicated stage business wise. All the plays have got lots of funny business in them, but Out Of Order has even more than usual. I won’t go into too many details about the story but there is a dead body in it, there’s a window that keeps crashing down and as usual there are three doors that keep opening and closing. And of all the plays, the choreography of this one is the most complicated.

Why do you feel this particular show has endured?

It applies to all of them. Take Run For Your Wife.It’s about a woman involved in a bigamous marriage, which is an awful shock because her husband isn’t just flirting with a secretary, he’s got another house, another home, children maybe. She’s devastated. I can happily see the funny side of that but that’s a situation that’s as dramatic and hopefully as funny today as it was when it was written in 1980. With Out Of Order as long as politicians carry on misbehaving then we’re fine. That will never end; misbehaving politicians will go on forever.

Have you made any changes for the new production?

It’s still set in a hotel, but it’s changed a bit because it’s now an old-fashioned hotel that’s been modernised in Westminster. And we’ve brought it bang up to date so it’s Jeremy Corbyn now and Theresa May. Not that they appear in it, but they’re referred to. I keep asking the younger people in the company about the references. For instance, there was talk of ‘the typing pool’ in the script and I said ‘Is typing pool a bit old fashioned?’ They said that yes it was so maybe we should change it to Facebook, which was a good idea so I made that change.

You’ve got a great cast. How important is it to get the right players for a piece like this?

It’s vital. Over the years I’ve been so lucky, working with actors like Donald Sinden, Richard Briers, Leslie Phillips, Bernard Cribbins, Michael Williams, Bill Pertwee, Tom Conti, Maureen Lipman, with all of them working as a team. Over the years I can only think of maybe three or four times where I’ve had an argument with anybody in the company and recently I can’t think of any. It’s a lovely cast I’ve got here. They all love the play and they’re a team. That’s one of the things I’ve learned over the years – mainly when I was working with Brian Rix, I think, in the very early days. You need a team. If it’s a drama, a comedy, a tragedy, a ballet, you need to work as a team – and maybe that applies to life too – to make it successful and to enjoy the success.

What kind of director would you say you are?

Again, it’s all about teamwork. When I started directing I didn’t realise how much I’d soaked up. It happened totally by accident. A director fell out of a revival of Thark by Ben Travers at Guildford so they rang me up and asked if I wanted to direct it myself. I said I’d never done it before but by that time I’d written One For The Pot and Chase Me, Comrade and they went ‘Come on, you’ve written these funny plays, you must be able to direct’ so I agreed to do it. When we did Thark with Peter Cushing and Ambrosine Phillpotts, a wonderful company, a producer was going to bring it into the West End and couldn’t raise the finance but we had the set and the company and he’d already booked The Garrick Theatre. He backed off, saying ‘I don’t have the money and I’m not going to do it’ so I thought ‘We’ve got the cast and the production’. I borrowed my mother’s burial money, my wife and I sold the car we had and I took the show into the Garrick. So then I became a producer! I didn’t want to be a producer, it just happened.

What are your memories of starting out in the business?

I was a boy actor from ages 14 to 20 and I was hardly ever out of work. I did lots of good plays and lots of tiny roles in the odd movie, plus a bit of television. I did my two years National Service in the army, then when I came out I answered an advert in The Stage, I got the job and thought I was joining a weekly repertory company. I got to this little town, which turned out to be more of a village, just outside Cardiff and discovered that the company did six plays a week across six days. I’d joined the last of the touring fit-up companies that did a different play every night. They broke me in gently with two plays the first week. They had a repertoire of 40 plays and we used to tour in a cattle truck throughout all the villages in Wales. It was fantastic and the audiences were marvellous. You’d arrive in this village which just had a few houses and maybe a pub and you’d think ‘Where is the audience going to come from to see a different play every night?’ but they’d come from miles around. One night we were doing a play about the life of Edith Cavell, who was shot by the Germans for being a spy, and I was playing the German officer who had to execute her. It came to the very end of the play and I had a line that went something like ‘Nurse Edith Cavell, you have been found guilty and you will be shot’. Before I could finish the line a chap in the front row stood up, grabbed me by the leg, pulled me off the stage saying ‘You dirty German bastard, you leave her alone!’ and started punching me in the face. Luckily the other actors came to my rescue. Anyway, I did that for two years, touring around in a cattle truck with the lovely actors and actresses and all the scenery. After that I did weekly rep in Blackburn, answered an ad for Brian Rix and I got a job in the tour of Dry Rot with John Slater and Andrew Sachs, after which Brian put me in his next West End play.

What did you learn from working with Brian?

That’s when I learned about teamwork. Do you know, in his 20 years at The Whitehall Theatre he only did five plays? That will never be achieved again ever and he’s never really been given the credit for that. He was made a Knight and then a Lord for all his services to charity but nobody will ever achieve what he achieved in terms of theatrical success. Today you’re lucky if you can get one actor to do one play for 20 weeks in the West End, but the actors grew to love him and some of them did three plays – which meant they were there for 12 years.

As the director as well as the writer are the words set in stone or do you allow any improvisation?

Nothing is sacrosanct, at least initially. With the first play One For The Pot, for example, we did a reading for Brian, then a rewrite. We went to Richmond for the first try-out, huge rewrite. Wolverhampton, huge rewrite. Windsor, rewrite. I’ve always played in the try-outs because I want to be on stage feeling the audience reaction, then I’ll do more rewriting. But by the time a new play gets to the West End the company know what’s been put into it and how the whole thing works. You still fiddle around with bits and pieces but the actors totally appreciate how it’s gotten to this stage. You’re giving them something that has already been done around the country, you’ve got all the laughs and removed all the rubbish and they’re getting a polished piece. It’s the same with this tour of Out Of Order because it’s tried and tested. It’s exactly the same choreography, the same moves and the same business as it was when we first did it 26 years ago. There are new references in it but the actors understand and appreciate it’s a proven thing. Once they get it on stage and hear the laughter they know how well it works.

How do you define a great farce?

It doesn’t necessarily apply to every farce but what I’m always looking for is the basic hub of a drama that could be turned into either a drama or a tragedy if another writer got hold of it. Take the basic premise of Run For Your Wife where there’s a taxi driver who, if one wife finds out he’s a bigamist or the other finds out he’s got another wife, all their worlds would crumble. If another writer had gotten hold of it it could have been a very moving tragedy, but my brain doesn’t work like that so it’s a comedy. The same applies to each of the plays. They’re not the sort of farces you might have gotten in the very old days because, although there’s comedy business in them, they all stem from the dramatic side of it. You want the characters to be real and performed as real characters who are dealing with predicaments. You don’t want a lot of silly business that doesn’t apply to the story. It’s the story that matters.

How do you hope audiences will feel when they leave the theatre at the end of Out Of Order?

That they’ve had the most wonderful evening. Something I’ve done with every play, which only a few years I discovered was how all the Greek plays were written, is that they are continuous action. They start off at a particular time and the length of time the audience is in the theatre is the length of the story. You lead up to the end of Act One with a nice, funny, dramatic moment, the curtain comes down, then Act Two starts off at the same moment. It means you don’t have to have the actors sort of explaining, via their characters, what has happened in the interim. The comedy line runs all the way through.

How does it feel when you’re sat in a theatre listening to audiences roar with laughter at something you’ve written?

It’s the most wonderful thing. I’ll never forget when we first did Run For Your Wife at the Shaftesbury Theatre. I wasn’t there for a Saturday night performance and after the performance Richard Briers, who was playing the lead, rang me up and said ‘It was terrible!’ because at a certain moment the audience just wouldn’t stop laughing. That’s the thing with these plays – dealing with the laughs. Luckily one surrounds oneself with actors who know how to deal with that.

And finally, what do you think of Brighton?

I love Brighton and I always have. I’ve done all the plays there over the years. Brighton’s gorgeous.

[syndicated]